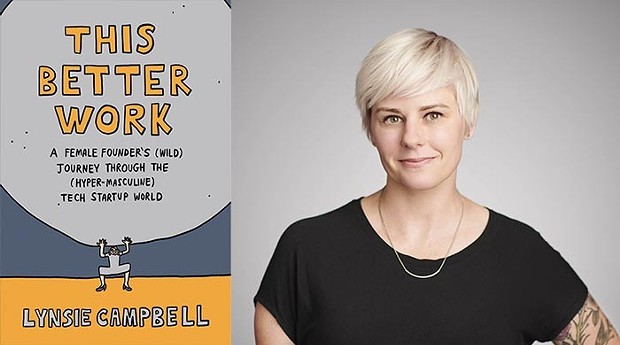

Photo: Kristi Jan Hoover

Lynsie Campbell

Lynsie Campbell started two companies in Pittsburgh, ticketing platform ShowClix, and bike-route sourcing app LaneSpotter. Each had a different outcome; ShowClix was acquired in 2017, and LaneSpotter shut down in 2019 after it ran out of money, due mainly to what Campbell described as a bad technical hire.

Her experiences at both ends of the startup spectrum in Pittsburgh are the subject of her new book This Better Work: A Female Founder’s (Wild) Journey Through the (Hyper-Masculine) Tech Startup World, where she calls into question a lot of the widely-touted and mostly accepted lore about the region’s startup scene. Contrary to what civic and tech leaders in the region would have us believe, Pittsburgh, Campbell says, is a really hard place for any founder to successfully launch a startup, even more so if that founder is a woman or a minority.

“Having gone through the startup ecosystem here, there are more failures than there are successes,” Campbell said in an interview. “And it’s one of the things that we just don’t talk about enough. Founders, whenever you experience those failures, you feel really alone because nobody else has actually shared them. What I wanted to do was really lift the cover on this and say, you know, some of this journey is going to be amazing and some of this journey is going to be really, really painful and it’s going to hurt, and you need to be prepared for that.”

She bristles at the idea that Pittsburgh boosters tout ShowClix as an example of the success of the region’s startup ecosystem. “I’m sick of Pittsburgh sugarcoating,” she said. “I’m tired of the city telling a startup story that isn’t necessarily true. ShowClix may have been a success story in regards to acquisition. For me, the founder, it wasn’t and I actually don’t believe it was the best outcome from our investors.”

Refreshingly, This Better Work doesn’t have the “girl boss” vibe of so many self-help books that offer dubious “business” advice. While she does offer solid pointers about what to think about when building a startup — hire people who can write and who care about your company’s mission, and, don’t overpromise just to land a big client — Campbell doesn’t suggest she has everything figured out. For example: chapter eight is titled “Surviving the Epic Fuckups,” where she details an event ShowClix ran for the Museum of Modern Art that crashed the ShowClix website, leaving many ticket-seeking Kraftwerk fans incensed.

Ultimately, she writes, how ShowClix handled the response — a full mea culpa — garnered positive press and helped add new clients. “The fuckups never end in the startup world,” she writes. “Some of them are big, and some of them are small. The one constant is that people are watching. How you respond to each crisis either helps your company continue to grow or hastens its demise.”

Campbell writes candidly about the parts of startup life she wasn’t good at, and the parts she hated — chief among them trying to raise funds — and the honesty and detail about her mistakes and the company’s mistakes, are what makes This Better Work a book that may actually help other founders learn what not to do. She’s brutally honest about the numerous mistakes she believes she made while trying to build LaneSpotter — not seeking partnerships with interested companies, for instance — and includes a lot of painful details.

“As I was working with my publisher, I was really struggling with how much personal information to include; I really wanted it to be more of like a business knowledge book,” Campbell said “But the more I started working with my publisher, they were like, ‘there’s just more to that, like you need to really tell the real story so that people can understand the context behind the advice that you’re giving.’ And that’s when it really just shifted and I started realizing that I have to be the most honest that I can possibly be if this is going to be helpful to others.”

Campbell name-checks several prominent figures in Pittsburgh’s startup scene; Jim Jen of InnovationWorks was ShowClix’s “champion” she writes; Ilana Diamond of AlphaLab Gear is a “smart, charismatic and empathetic leader,” who she wishes she’d met earlier in her career.

But she’s much less complimentary to startup accelerator AlphaLab, which spun out of Innovation Works in 2008. Campbell was accepted into AlphaLab in 2017, but she was disappointed with the experience.

“The vibe at AlphaLab was terrible. Nothing about it fostered creativity,” she writes. With the possible exception of launching hardware accelerator AlphaLab Gear in 2013, AlphaLab has done little to evolve since its founding, Campbell said. “They’re fine with the status quo, their program hasn’t changed, their mentorship hasn’t changed,” she says. In the book, she describes returning to an AlphaLab event in 2017, finding many of the same faces, including one who made an uncomfortable advance toward her.

Campbell says a big problem in the Pittsburgh startup ecosystem is the focus on seed stage investments, which end up being quite low compared to other cities. She points to the way the local media and the region’s boosters touted Pittsburgh’s rank of 23rd out of 100 Top Emerging Ecosystems on Startup Genome’s 2021 Global Startup Ecosystem Report. But a close examination of the figures shows Pittsburgh’s startup scene still lags way behind in the amount it invests in early-stage startups.

“Everyone was so excited that we ranked 23rd, but nobody took the time to talk about the median seed stage investment number,” Campbell said. In Chicago and Philadelphia, the report found a median seed stage investment amount of $550,000. The global average is $480,000. In Pittsburgh, the seed stage median investment is $75,000. ”If that’s not a glaring problem, I don’t know what is,” she said. “We are only investing at that really early stage, and then leaving people hanging when they need that next round of funding the most. We’re also not giving them enough money to start off with.”

Campbell says if she were put in charge of overhauling Pittsburgh’s startup scene, she would take some of what she learned in her experience with Boulder-based startup accelerator Techstars, where she worked when trying to launch LaneSpotter. First and foremost would be improving the mentoring network, so entrepreneurs who wanted to help founders in Pittsburgh could give much-needed — and relevant — advice, so that startups have a plan for where to go when they’re out of the seed stage.

Earlier this year, Campbell joined venture capital firm The Fund as a general partner in its Midwest region. “I’m sitting in on pitches every week with startups from Detroit, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, all in the midwest,” she said. “I have not been able to write a check to somebody in Pittsburgh yet because nobody here can get a lead investor. We don’t have a set of companies that are established who are willing to take the risk on the earlier stage companies and be that first customer.”

As for her next move, Campbell said she’s hoping to be able to help improve numbers — especially for women — in Pittsburgh startups. “I want to be the voice of overlooked founders in Pittsburgh,” she said. “in whatever capacity and wherever that leads me over the next five years.”

Campbell said she hopes the future of Pittsburgh’s startup community will look more diverse and have more people who take nontraditional paths on their startup journeys. “We need more people and more perspective making the decisions around who’s getting the money in this city,” she said. “There are still a lot of people around those tables that are the same people who have been there for a long time.”

Credit: Source link