In 2015, Rajan Bajaj suddenly forgot the basics of dribbling. The young lad, who represented his home state Rajasthan in the basketball nationals during his school days, started playing like a rookie. After working for Flipkart for just 10 months, the IIT-Kharagpur grad quit his maiden job and started a fintech venture in January.

“I loved my job at Flipkart,” he confesses. What, though, he loved most was starting a business. Coming from a middle-class family in Alwar, Bajaj’s father was an engineer and mother a teacher. “Nobody in the family ever had any business background,” he recalls. The idea of turning an entrepreneur germinated during college. And for four long years, he kept mulling. “If I didn’t leave and start then, probably, I would have never done it,” he says, explaining why he short-circuited his stint at the product team of Flipkart. It was high time to make a shot rather than keep aiming at it. And he knew he could do it.

Till early 2015, Bajaj had excelled in studies, and sports. He had perfected the art of running while dribbling; scoring three-point baskets was done without any fuss; and speed and control over the ball gave him immense confidence. Back in 2015, when he was ready to take the plunge, he expected a rub-off in entrepreneurship. The game was on.

In April 2015, a month after leaving Flipkart, Bajaj started a rental startup called Mesh. While the name was inspired by a book—The Mesh by Lisa Gansky—that he read during the second year of his college, the business idea was influenced by the Airbnb kind of startups which were driven by the idea of sharing economy. “Houses have been lying around for ages. Nobody noticed it. And Airbnb just made something out of nothing,” he says.

Mesh, too, was trying to build something out of nothing. Bajaj started with gaming consoles, camera, bicycles and DVD rentals in Bengaluru; built a website, promoted it on platforms like OLX, and started delivering the orders on his bike. “It was a very hacky thing to do,” he says. The business proposition was great: Why buy second hand when you can have it on rent? The business, too, gathered decent pace—after two months or so, Bajaj had to hire a delivery boy to take care of the rising orders.

Though the business grew, so did the problems. After a few months of dribbling, Bajaj realised that he was not able to score. He forgot the basics: One must use fingers, not palm, to control the ball. In a fast-paced game like basketball, the trick is control. Bajaj, though, didn’t have any control from Day 1. Reasons were many. The market for rentals was not big. Second, insurance, logistics and damage were difficult to track. And last, he might have been too early with the rental business.

Bajaj then quickly pivoted to car and bike rental, another shared economy business model. By September 2015, the business did show some promise. Mesh used to get 20-30 orders every day, but it brought along with a mess of a different kind: Managing cars and accidents. The young founder again pressed the pivot button and moved to a marketplace model. After a few months, it, too, started losing steam. “The business couldn’t scale,” he rues. In fact, none of the previous ventures he dabbled into scaled. Now Bajaj made a last desperate attempt. He shifted to furniture rental. Unfortunately, it too, bombed.

By December 2015, and a few months of successive and quick pivots, Bajaj thought he had figured out his sweet spot. Mesh got changed into Buddy, a buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) venture. “The model was doing well globally, and we thought it would work out in India,” he says. There was another reason. While in college, Bajaj wanted to get into investment banking. Buddy was his way to live his finance dream. Buddy, though, had its share of blues. State Bank of India already had a product with the same name. Bajaj had to rename Buddy to Slice Pay.

For the next three years, till 2018, the venture ambled. Then suddenly, in 2019, Bajaj pivoted to credit cards. Reason was simple. BNPL couldn’t scale because merchants were not willing to pay higher commission. The model, Bajaj underlines, only works when merchants pay higher commission. “By 2018, we realised that BNPL is the worst product experience,” he says.

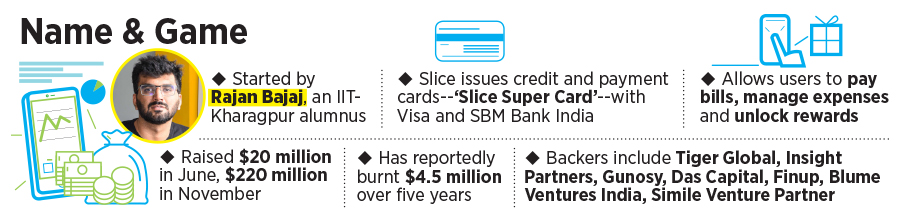

For three years, 2016 to 2018, Bajaj again forgot the second basic of dribbling. Don’t bounce the ball too high. In 2019, he switched to cards. Slice started issuing credit and payment cards—‘Slice Super Card’—with Visa and SBM Bank India. The focus was on millennials and Gen Z, and Slice allowed them to pay bills, manage expenses and unlock rewards.

The move has finally turned out to be rewarding for Bajaj. In June last year, he raised $6.07 million in a pre-Series B round of funding. Twelve months later, he got another $20 million. In November 2021, it was slam dunk. The first-time founder raised a staggering $220 million in Series B round, which pole-vaulted Slice to over $1 billion from under $200 million.

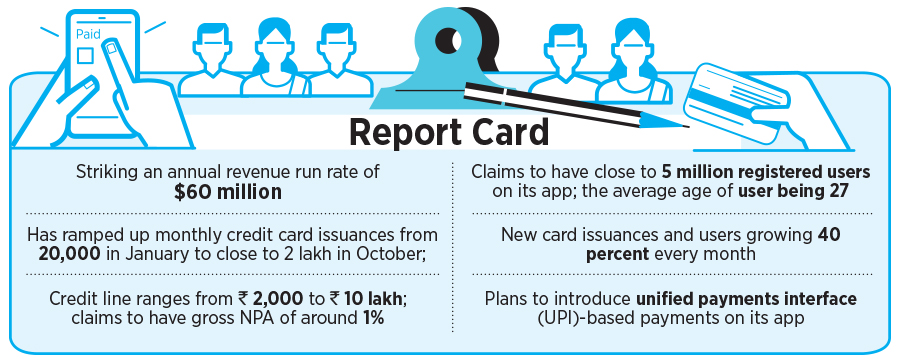

The ‘credit card challenger’ seems to have done enough to justify its billing. It counts Tiger Global, Insight Partners, Gunosy, Das Capital, Finup, Blume Ventures India and Simile Venture Partner among its long list of marquee backers; claims to have 4 million registered users on its app, and strikes an annual revenue run rate of $60 million. The startup is now getting ready to get deeper into the payments game. “We are launching UPI (unified payments interface),“ says Bajaj. “We plan to take a huge slice of consumer businesses in India,” he asserts. What this essentially means is a slice of cards and payments, of UPI, investments as well as commerce.

Industry experts are not surprised with the fast pace of growth and the way Bajaj is slicing the fintech market. Shivathilak Tallam, vice-president at Unitus Ventures, explains what has worked for Slice. Credit has always been a challenge for the segment that Slice operates in—Gen Z (those in early 20s) and millennials. “Startups like Slice is making this demographic access credit easier than before,” he says. The startup, he underlines, banks upon two factors. The card is the innovative way to slice the purchases into cost-free EMIs. This is a major driver in the current economy and consumer purchase power. “Tech-driven sourcing and on-boarding is helping accelerate adoption within consumers in a seamless manner,” he adds.

What, though, explains investors’ bullishness, especially Tiger Global in backing Slice is an interesting set of data. India, points out Mrigank Gutgutia, associate partner at homegrown consulting firm Redseer, is a hugely under-penetrated market when it comes to credit cards. For an investor, betting on a startup is based on two components. The first is the macro story, which means that the sector in which the company operates in. It has to be good, robust, and in the right place at the right time. Post-Covid, fintech ticks all these boxes. Besides, India has an estimated 30 million active credit card users, or people with at least one credit card, says Gutgutia. Now compare this to smartphone users: Over 500 million. “The headroom for the growth of credit cards is massive,” he says.

The second component of any investment thesis, Gutgutia underlines, is the way the company getting funding has grown. “Slice is bridging that credit divide, has buy now pay later embedded in it and has found the product-market fit,” he says, adding that the fintech startup is bringing millions of users who have zero credit score into the mainstream. Tiger, he reckons, is not betting on what Slice is today. “They are betting on what Slice could be in five years,” he says, alluding to a host of cross-selling and many financial services and products that Slice might get into in the future.

Digital credit startups like Slice also have an edge over biggies like Paytm. While, for Paytm, the lending business is not big, Slice has always led a digital credit existence, says Gutgutia. The big plus to investors, he underlines, is the pace at which it is growing as well as monetising. “The future looks promising,” he says.

He is quick to add a word of caution, though. The credit lending market is getting hyper cluttered, with every player chasing the same set of consumers. While Slice has differentiated itself in building a robust underwriting method of growing its business, the magic sauce is customer stickiness. Catching them early is not the game. Staying with the young catch, cross-selling a host of services and remaining with the user for a longer period will decide the winners. Can Slice do it?

Bajaj reckons he has got a firm hand on the pulse of the Gen Z users. “We are focusing on creating a huge impact,” he says. What the young founder needs to remember, though, is again one of the basic rules of dribbling: Don’t bounce the ball too high.

Click here to see Forbes India’s comprehensive coverage on the Covid-19 situation and its impact on life, business and the economy

Credit: Source link