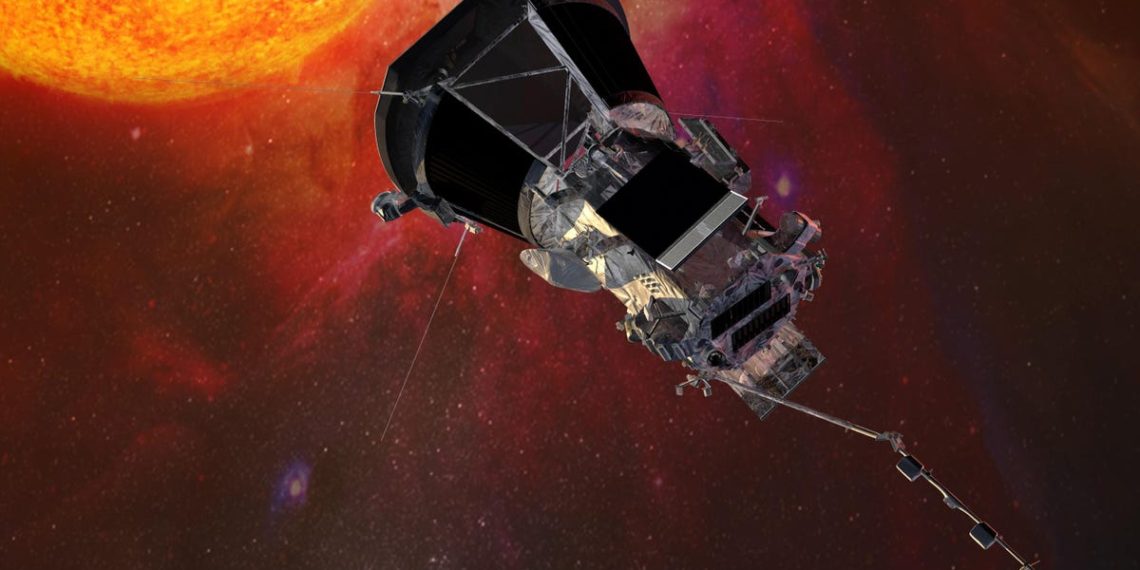

Artist’s concept of the Parker Solar Probe spacecraft approaching the Sun.

Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

Is human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit a thing of the past? Will space tourism profit and expand in low-Earth orbit while the rough and tumble exploration of space beyond the Moon continue to be carried out via robotics?

These questions cut to the heart of “The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are The Future of Exploration,” a thought-provoking new book co-authored by astrophysicists Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees.

Although such arguments aren’t necessarily new, the authors make some salient new points that bear repeating here.

—- Human space travel remains dangerous.

High energy solar and galactic particles are rife throughout the solar system. Beyond Earth’s Van Allen radiation belts, astronauts are particularly vulnerable to radiation from such particles.

For each month in space, human bone density can lessen by as much in 1.5 percent in weight-bearing locations of the body such as the hips and knees. Astronauts spending six months en route to Mars, would receive at least 60 percent of the total radiation dose recommended for a full career, the authors note. The return trip home would push them over the limit, even without a sudden increase from solar storms or flares, they note.

—- In contrast to human space exploration, non-human robotic explorers have safely and efficiently reached the outer edges of our solar system.

“Since its creation in 1958, NASA has spent about 60 percent more on human exploration than on robotic investigation of the cosmos,” the authors write. “We should note that the human exploration of space has so far extended only to the Moon…”

The End of Astronauts

Harvard University Press

—- Space-based telescopes need not be serviceable by humans.

Although the Hubble space telescope wouldn’t have been operational without the ability to rescue it from what Goldsmith and Rees term “an otherwise fatal manufacturing defect,” they do note that the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, which manages the Hubble “has said that the total cost of the five astronaut repair missions would have paid for building and launching seven replacement telescopes.”

It’s hard to know whether this would be the case, given rising costs for instrumentation and space observatories in general. But the point is well taken. And perhaps that’s one reason the Hubble’s follow-on observatory, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), was never designed to be serviced by human astronauts, at least.

From its current solar orbit some one million miles from Earth, the James Webb is currently out of reach of a crewed service mission. But thus far it has proven to be well on track for full science operations set to begin this summer.

—- Artificial platforms for space colonies would hardly be Valhallas.

Artists often depict space colonies as exciting and attractive, resembling a holiday resort, or some other realization of our hopes for a near-perfect environment, Goldsmith and Rees write. But the authors note that this is likely not to resemble the reality of such space colonies constructed in interplanetary space. They note that there will be great difficulty and danger in maintaining such huge artificial structures in space, as well as the technical challenges involved in their construction.

—- But space platforms would potentially allow billions of people to live in space.

As Goldsmith and Rees point out, “in his 1997 book “Mining the Sky,” the cosmo-chemist John Lewis lamented that “as long as the human population remains as pitifully small as it is today, we shall be severely limited in what we can accomplish. Lewis stressed that ‘human intelligence is the key to the future…. Having only one Einstein, one da Vinci, one Bill Gates is not enough’.”

The implication is that maximizing our human potential might require increasing the human population a hundred-fold. Space platforms would offer humans a sustainable way to increase our numbers and thereby “roll the die” so that geniuses would become more commonplace. Who knows if such a scheme would work? Instead, it would just be easier to reengineer our brains artificially to make such once in a lifetime geniuses more commonplace than we could ever imagine.

This whole argument is a bit tangential to the book’s focus of why robots should prevail in space, at least for the time being.

Goldsmith and Rees make a compelling case for robotics over astronauts at least in the short term. But let’s hope that 100 years from now, time and technology will allow us to have both robust human interplanetary spaceflight and state of the art robotic space science and exploration.

In the short term, however, it probably does make good sense to emphasize solar system exploration via robotics as has been brilliantly done by the national space agencies over the last 65 years. It’s truly amazing and how much has been accomplished with so few dollars.

In time, let’s hope that there is a meeting that that that there is a merger of sorts between the kind of robotics that can complement our human aspirations to travel into interstellar space in ways that are incomprehensible at present.

Credit: Source link