Real estate startup Pacaso had quite a year. Launched one year ago, it already has $215 million in funding and a $1 billion “unicorn” valuation. Reportedly, the company has set a record for being the fastest company in U.S. history to have reached unicorn status.

Why should Healdsburg care about a surging company in the Big Tech sector? Boom or bust, it’s not our business, right? Well, Big Tech is in our real estate market, and that is very much our business. Pacaso is deploying enormous financial and legal resources to achieve its real estate goals here in Healdsburg and in a number of other attractive destinations across the U.S. We desperately need to understand what that means for our local housing markets, our agricultural lands, our neighborhoods, our community character and our social values. Let’s understand and take action to protect Healdsburg and our County.

What does Pacaso do?

Pacaso purchases luxury homes in destination locations, markets them online and packages up to eight purchasers into an LLC that owns the specific home. Owners and their “guests” are limited to short term stays of two to 14 days at a time. And no more than 44 days a year, total. Pacaso handles the time scheduling, financing, administration, management and even guarantees the loans on the property. Its ongoing business is comprehensive management of the properties.

What is Pacaso’s impact on agriculture, neighborhoods, housing and community?

Healdsburg (has two active listings), Dry Creek Valley, the cities of Sonoma and St. Helena are known targets. As of June, Pacaso had paid an average of $4.1 million for its 14 homes in Napa and Sonoma counties. Neighborhoods are fighting Pacaso’s vacation home intrusions. There are reports of escalating housing prices and rents. We need full and updated data.

Although the Pacaso business operates like a short-term vacation home, it circumvents both the permitting process and the transient occupancy tax (TOT). Why is TOT important to collect? The tax paid by visitors helps fund projects that benefit the community as a whole. These include public safety, transportation, libraries, public parks, infrastructure improvements, and historical and environmental preservation projects.

Pacaso has two vacation homes ($677,000 for one-eighth share) in Dry Creek Valley. Our Agricultural Zoning Policy for Land Intensive Agriculture and our Agriculture Element of the General Plan require preservation of agriculture and only allow commercial uses that are ancillary to agriculture. These Pacaso commercial uses violate ag preservation policy and zoning and should cease.

Pacaso owns or manages five homes in St. Helena. St Helena has banned Pacaso’s fractional homeownership model, citing an ordinance prohibiting timeshares. Pacaso aggressively filed a federal lawsuit against the city, a silencing/bullying tactic backed by its huge startup financing.

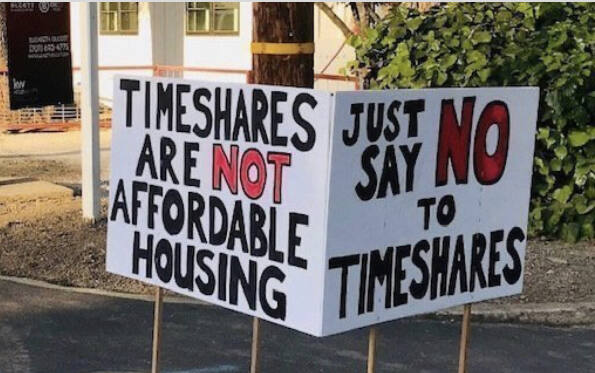

Is this a timeshare business?

Pacaso exploits a technical argument to dispute that its properties are timeshares. Pacaso claims it is offering “fractional ownership” of single-family homes, not a “timeshare.” It fears the “timeshare” designation would run afoul of city zoning prohibiting timeshares, plus it evokes the stigma attached to timeshares in general.

Actually, multi-ownership of a single family home is consistent with “timeshare” history. Timeshare – Wikipedia Today, many timeshare properties involve titled ownership. The real difference between timeshares and fractional ownership is that fractional ownership is more exclusive (more usage, fewer owners, more expensive). Differences Between Fractional Ownership and Timeshare (andysirkin.com)

Actions to take

•Speak out on Pacaso’s exploitation of cities, neighborhoods, rural lands

•Petition · STOP THE TIMESHARE TAKEOVER OF DRY CREEK VALLEY · Change.org

•Stop Pacaso Now

•Ask the Board of Supervisors, your city council and your state legislator to take action

•Uphold General Plan polices protecting ag

•Investigate and uphold zoning (LIA, vacation homes, timeshares)

•Officials should fill any loopholes with new legislation for effective enforcement

Yael Bernier has farmed in Dry Creek Valley for 45 years. She is current president of the Dry Creek Valley Association and believes strongly that we must preserve our agricultural lands now and into the future for generations to come.

Janis Watkins grew up in rural Sonoma County, where her father was a UC farm advisor. She practiced law here for many years and volunteers with the environmental nonprofit Sonoma County Conservation Action.

Credit: Source link