In recognition of World Emoji Day, which occurs on 17 July each year, now is the perfect time to explore the history of emojis. The emoji landscape is often attributed solely to the work of Shigetaka Kurita in 1999. Nevertheless, the pioneering work of Nicolas Loufrani and the Smiley Company has significantly shaped the history of emojis, as detailed in his interview on the company’s official website. The rich tapestry of emojis’ evolution began in 1996, when the Smiley Company licensed a simple Smiley pictogram to Alcatel, predating all other phone manufacturers, including NTT Docomo.

By 1997, Nicolas Loufrani had embarked on developing a more nuanced form of digital expressions, creating an extensive series of logograms capable of conveying a broad spectrum of activities and emotions. By 1999, Nicolas Loufrani and the Smiley Company had launched a series of 256 icons, including 42 conveying emotions, far surpassing the initial set created by Shigetaka Kurita in terms of clarity, scope and diversity.

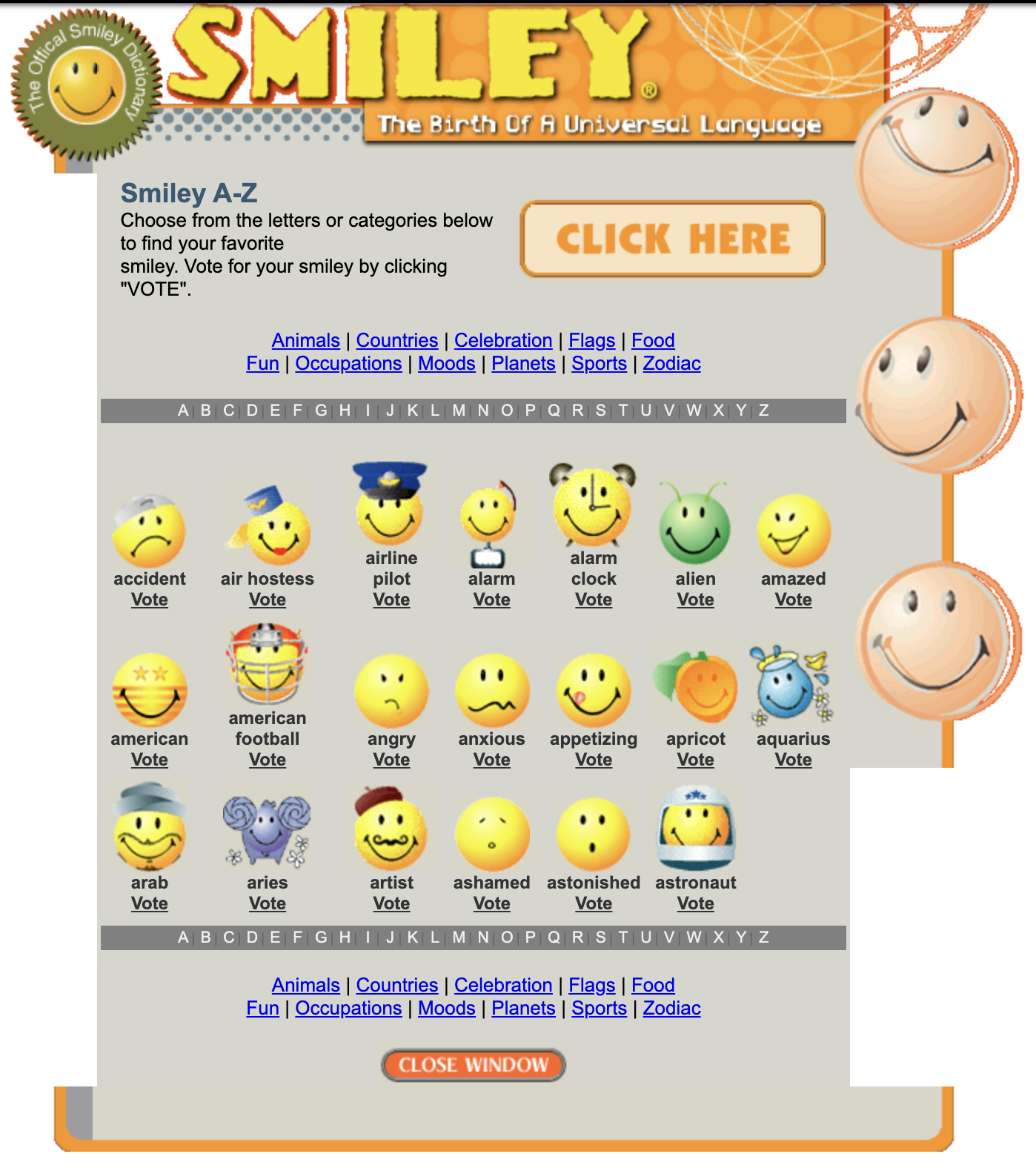

The Smiley Company’s icons were categorised into 11 categories in total, comprising moods, flags, countries, fun, food, planets, sports, occupations, animals, celebrations and zodiac. Nicolas Loufrani’s Smileys were not merely pixel symbols; they were a comprehensive, easily identifiable logographic system created to enrich communication.

Shigetaka Kurita’s emojis were not initially sorted by categories. However, Kurita’s icons broadly fall into eight categories, namely weather, sports, travel, places, objects, symbols and zodiac, with just a handful of human emotions. Each of Kurita’s emojis is rendered within the constraints of a 12 x 12 pixel grid, focusing largely on symbols and activities, presenting a smart solution to the mobile technology limitations at the time.

Nicolas Loufrani has described Kurita’s emojis as ‘incredibly beautiful’, demonstrating ‘Japanese industrial design at its best’, pointing out that they deserve their place in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He has also compared them to Suzane Kare’s pictographs developed for the first Apple Macintosh, a set of pixel icons that depict various technological devices and processes.

By contrast, the Smiley Company’s icons were created to capture a wide array of human activities and emotions from the outset, utilising the full potential of nascent 3D graphics and digital colour displays. This broader categorisation and emotional range laid the foundations for what emojis have become, affecting not only design but influencing the very concept of digital communication itself. Looking at the Smileys from 1999, it is clear that the emojis launched on Apple smartphones in 2008 were influenced by Smiley’s rather than Kurita’s icons. Other companies followed suit, with the likes of Google, WhatsApp and Samsung all launching their own style of emojis.

The first Smiley was launched by Alcatel in 1996, having been licensed to the cell phone company by the Smiley Company. This first iteration was merely a pictogram incorporated in a welcome message, accompanied by the words ‘C’est moi’ (French for ‘It’s me’), and could not be sent via text message.

In 1997, Nicolas Loufrani developed a range of 3D Smileys incorporating a white light, orangey shadow effect, with no black outline. It is plain to see that the emojis of today look closer to Loufrani’s creation than Shigetaka Kurita’s.

By 2003, Nicolas Loufrani had developed a staggering 887 original Smileys. In addition to the Smiley Company’s initial 11 categories of icon, Nicolas Loufrani added 12 more genres, including celebrities, clothes, flowers, instruments, nature, numbers, objects, religion, science, transportation and weather. Nicolas Loufrani also expanded the moods category, covering some 130 human emotions in total.

Over the course of the next two years, Loufrani doubled the number of icons and categories, setting himself the target of developing a new icon each day. Witnessing the positive impact of his creations on the public, Nicolas Loufrani spearheaded the Smiley dictionary’s continuous evolution, making it possible for people to vote for their favourite Smiley icons. He would check the results daily, assessing which icons were used most and reading and responding personally to comments from fans.

In 2008, when Apple launched its first set of emojis in Japan, the 471 icons bore a striking resemblance to the Smiley Company’s icons in terms of both broad categorisation and expressive depth. Apple’s emojis consisted of a series of 77 round, yellow icons with white light, an orangey shadow effect and no black outline, with some in monkey or cat form. Apple’s series was close to Nicolas Loufrani’s 1999 Smileys, albeit with slightly different traits, inspired by Japanese manga and anime culture, such as a long white line for teeth.

Proud of the enthusiasm he had generated, Nicolas Loufrani pledged to continue to develop more of what the public wanted, continuously developing the Smiley Company’s graphic style and creating products that customers love. The SmileyWorld toolbar incorporated thousands of icons that were categorised in different genres, enabling users to insert these digital stickers in any digital text in both still and animated form.

Recognising the vast potential of digital icons to transcend traditional barriers to communications, the Smiley Company licensed its icons to phone manufacturers and consumer product brands. Smiley icons were initially used as screen décor on devices predating the modern smartphone, using a monochromatic pixel form.

As technology evolved, so too did the Smiley Company’s offerings, with the company producing new versions of its icons that were available as gifs on the official Smiley dictionary website. However, as Nicolas Loufrani points out, it was largely thanks to Unicode that emojis could be established as a universal language on a massive scale. Members of this consortium, including the likes of Google, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and IBM, helped to crystalise the Smiley Company’s vision of enhancing digital communication in ways that transcend the limitations associated with traditional ASCII emoticons.

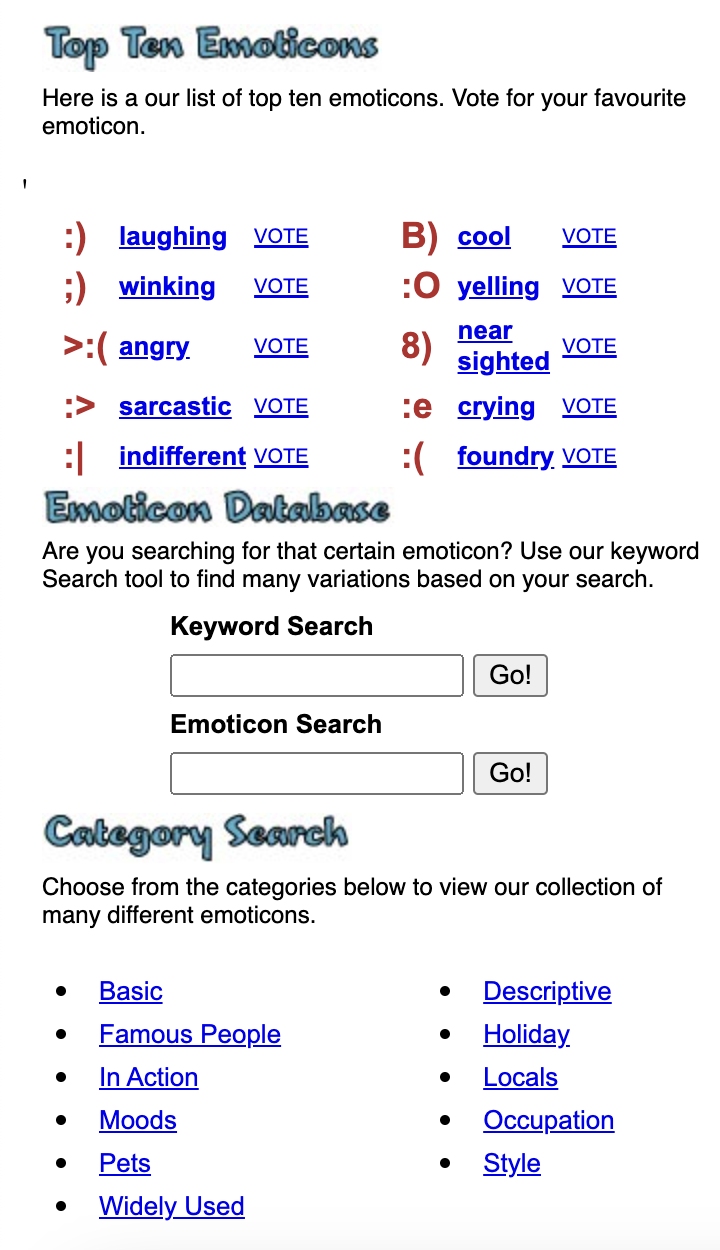

Although ASCII emoticons did improve email and chat room dialogue following their introduction by Scott Faulman in 1982, their usage was cumbersome, requiring users to mentally tilt their heads to read each expression. They were very conceptual; for example, imagine that the emoticon for Charlie Chaplin was CI:=)

The Smiley Company developed a full dictionary of graphic emoticons, collecting and reviewing hundreds of existing ASCII icons from the web, while systematically removing the dash sign for the nose which was absent in the original Smiley.

Recognising the limitations of ASCII emoticons, Nicolas Loufrani and his father, Smiley trademark creator Franklin Loufrani, initiated the next bold step towards elevating this universal digital language by launching an alphabet of colourful, upright Smiley fonts capable of being downloaded across various digital platforms. The move saw the official Smiley dictionary become available on the internet for the first time, with the platform translating the old-school language into a new universal language.

The idea behind the Smiley dictionary was to provide a comprehensive resource that was not only categorised by emotions, objects and activities but alphabetically too. The Smiley dictionary’s launch laid the foundations for establishing a global visual language capable of being shared and understood universally, with the Smiley gifs designed to be compatible with all computer brands and exchanged across all email services and instant messenger platforms.

Over the years, there has been much speculation over the true emoji creator. Although Nicolas Loufrani is not considered the emoji owner or creator, in a 2017 interview with Vice, he highlighted the obvious influence that Smileys had on emojis. Although Shigetaka Kurita has been hailed as the emoji’s creator, in reality, the story is more complicated and nuanced. The emojis that are commonly used today are inarguably inspired by Loufrani’s work with the Smiley Company.