The UK is today home to nearly 200 accelerators, drawing on the model pioneered in California by Y Combinator — an early backer of Airbnb, Dropbox and Reddit.

Unlike VCs, accelerators gamble on very nascent founders — often before they even have a product or team. That means picking winners is especially difficult, and it’s tricky to know which programmes are performing.

To put them to the test, we’ve analysed the portfolios of the nine most active UK accelerators between 2011 and 2018. They’re ranked by the percentage of portfolio companies that have since gone on to raise external funds. We’ve also looked at the percentage of startups that have raised more than £40m and are still active.

This analysis, created in conjunction with Beauhurst, is particularly noteworthy given many accelerators take government and EU funds.

The results are as follows:

On average, these nine accelerators see strong survival rates, with 79% of the attendee pool still registered on Companies House. This beats the standard success rate for UK startups, where only 40% survive their third anniversary.

The odds of getting VC backing are also good. On average, 55% of the startups sampled got external funding after attending, according to Beauhurst.

Nonetheless, it’s still early days for finding superstars — just 3% have gone on to raise north of £40m.

Within this, the best performing accelerator was Tech Nation’s UK growth programme Upscale, founded in 2016. Their portfolio companies were most likely to get funded and to raise a serious round.

This makes sense given Upscale acts more like a VC by only accepting founders at Series A, counting alumni like Improbable, Bloom and Wild, Dext and Depop.

Entrepreneur First also ranks well among the generalist, early-stage accelerators. The programme told Sifted that just over 60% of those who presented at Demo Day in London (2011-18) went on to raise external capital.

Founders who reach Demo Day are already considered the cream of the cohort. Just 40-50% of those accepted by Entrepreneur First are invited to form companies to present at Demo Day, after three months.

Notes on the study

We’ve attempted to standardise the data by comparing those with similarly sized portfolios across a fixed time period.

However, it’s worth stressing that the accelerators in this sample were not all founded in 2011, meaning some portfolios are less mature. In particular, the data for London & Partner’s Business Growth Programme and Natwest’s Accelerator only accounts for their 2018 cohorts.

It’s also worth highlighting that these accelerators have very different functions, and cut across various specialisms.

Meanwhile, the study only monitors the ‘most active’ accelerators between 2011-18 — meaning those who sponsored the most startups in that period. But since then, other notable candidates have picked up steam — including Antler, Founders Factory (FF) and Barclays.

For reference, Founders Factory has accelerated 100+ startups between 2015 and now. 85% of these are still alive, according to Beauhurst. In addition, the fund has counted eight successful exits so far.

Similarly, Barclays Accelerator has backed over 100 fintech startups to date — 76% of which have gone on to raise external funds.

To accelerate or not to accelerate

Beyond looking at funding success, there are other ways to judge accelerators’ impact.

For instance, the ICURe — targeting researchers and PhD students with up to £35k — looks closely at how many teams get licensing agreements (18%) and value for money (£3.14 created for every £1).

Some non-UK accelerators prefer to look at revenues. Wilco, a French accelerator, claims 25% of their early-stage startups reach €1m in revenues within the 3 years of attendance.

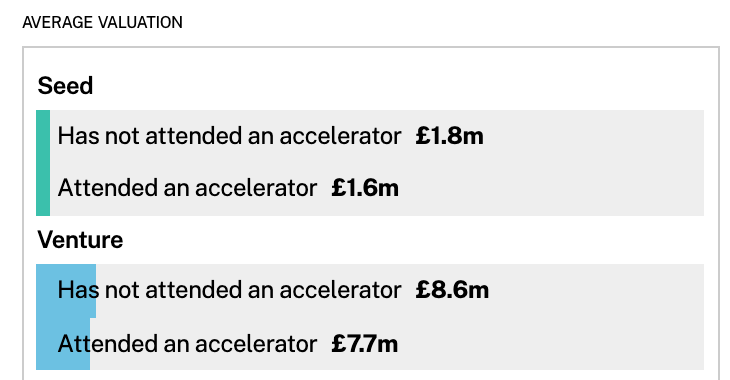

In addition, Beauhurst analysed accelerators’ impact on valuations. But it wasn’t flattering — at the seed and venture stages, startups that have been accelerated had lower pricetags on average than those who had not.

This leveraged a sample of 1,500 UK accelerator attendees between 2011 and 2017, providing a snapshot of accelerators overall rather than their individual achievements.

Another worthy indicator is how founders rate their experiences of different accelerator programmes.

A study commissioned by the government in 2019 surveyed founders on how helpful they found their accelerator programmes. Overall, 64% of founders felt attendance was vital to their success.

However, when approached by Sifted, the study organiser declined to share how each individual accelerator was rated, per data protection laws.

A maturing space

Most UK accelerators still haven’t produced an expanse of impressive alumni, with some still too young and others simply picking too many misses.

But the last two years have shown evidence of a sea change.

Entrepreneur First, which began in 2011, has started to see a maturing set of investments, with companies like Accurx and Permutive both raising double-digit rounds last year.

It also secured its biggest exit ever last year when PassFort was bought by Moody’s — beating the previous $150m record set by Magic Pony.

It may also be reassuring to note that Y Combinator, which began in 2005, waited 13 years for its first portfolio company to IPO.

The pace is now rapidly picking up. Last year — nearly two decades after it was founded — the accelerator watched 10 companies graduate into the public markets.

That may soon involve more European startups, who can now also attend Y Combinator from home.

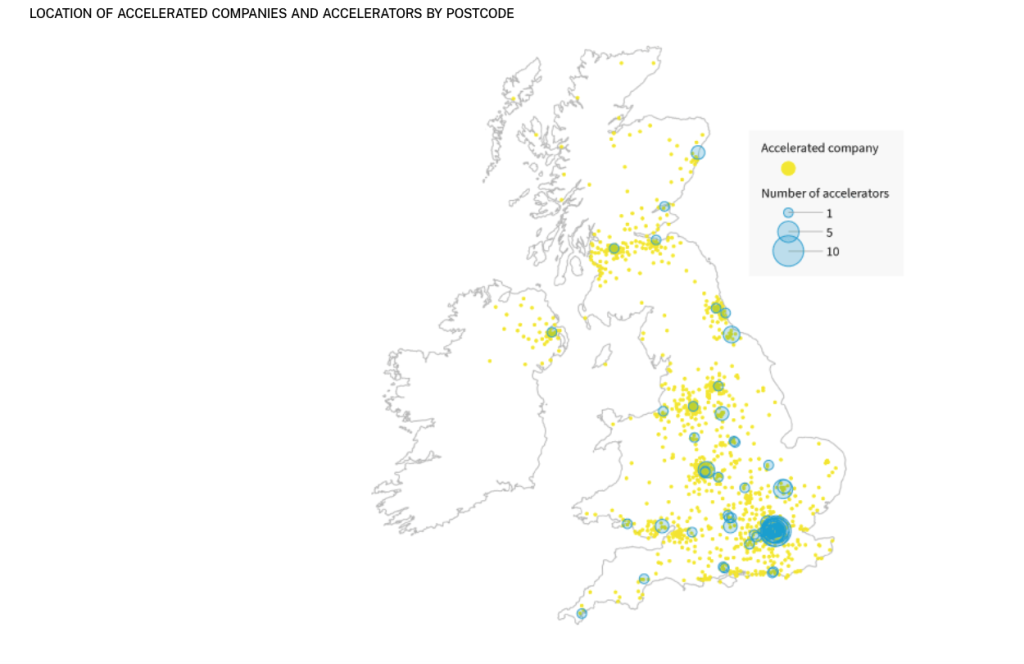

Despite Y Combinator bringing fresh competition to local accelerators, this could have far-reaching benefits. One study found that accelerated startups have a positive impact on the local ecosystem, including employment.

Resources

- The best accelerators for women — Sifted

- The best accelerators for health — Sifted

- Biggest accelerators across the UK — Beauhurst

- The issues with corporate accelerators — Sifted

- Accelerator: Friend or Foe? — Sifted

Isabel Woodford is a senior reporter at Sifted. She tweets at @i_woodford

Credit: Source link