Since August 2021, malware peddlers have managed to spread four families of Android banking trojans via malware droppers introduced in Google Play. They did it by employing a series of tricks to bypass the app store’s restrictions, evade automatic detection, and trick users into believing the apps they downloaded are legitimate and innocuous.

According to researchers from fraud prevention outfit ThreatFabric, the malware droppers posed as PDF scanners, QR code scanners, cryptocurrency apps, self-training, authenticator, and security apps, and were collectively downloaded over 310,000 times.

The silver lining in this situation is that not all the users who downloaded them were ultimately saddled with banking trojans: the delivery of the malware was reserved only for users in specific regions of interest and was performed manually.

Source: ThreatFabric

The tactics employed by the attackers

The different banking trojan families delivered through these campaigns are dubbed Anatsa, Alien, Hydra and Ermac. Each of them targets a multitude of banking, cryptocurrency-related, mobile payment and email apps.

The campaigns generally unfurl like this:

1. Malware peddlers introduce droppers into Google Play, masquerading as helpful apps that are actually working (and thus incentivize users to leave positive reviews)

2. Once these apps are installed and run for the first time, they send device information (device ID, device name, locale, country, Android SDK version) to a command and control (C2) server

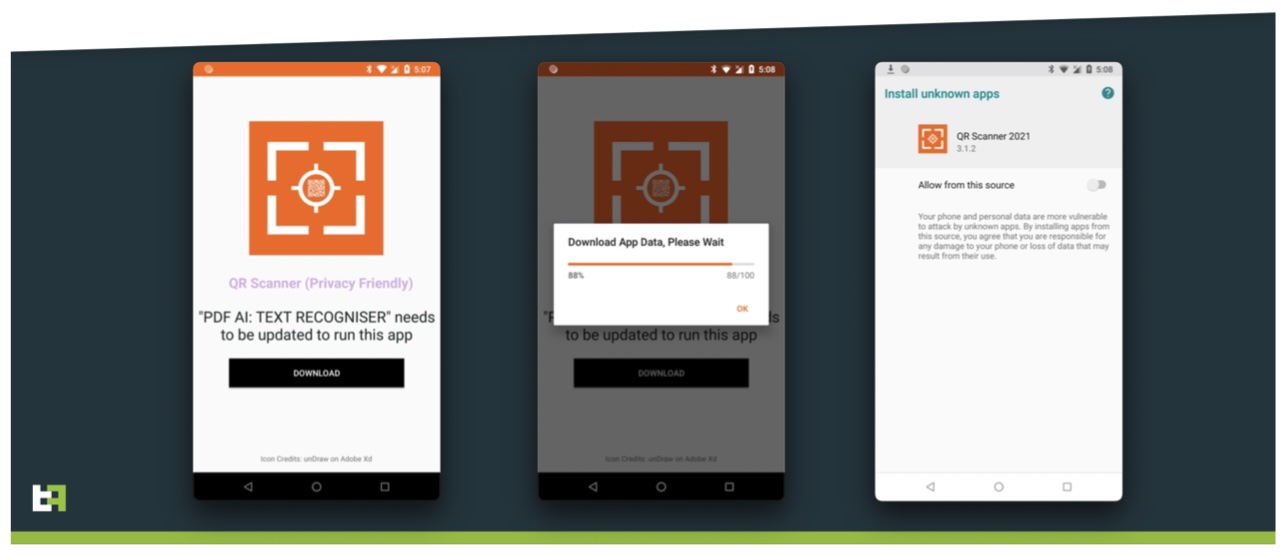

3. Depending on that information, some users are asked to update the app so they can continue using it

4. If they agree and brush aside warnings that downloading content from a source that isn’t Google Play is a dangerous proposition, the banking trojan (still masquerading as the initial app) is installed on the device and asks for a wider set of permissions, which will allow it to steal credentials by capturing everything shown on the user’s screen and logging keystrokes, and the attackers to access the device remotely.

Source: ThreatFabric

The crooks behind these campaigns have figured out a number of tricks that prevent the droppers from getting immediately detected/blocked by Google Play and AV solutions, and the malicious payloads from landing into security researchers’s hands.

They have:

- Significantly reduced the malicious footprint of dropper apps (they don’t ask for specific suspicious permissions, e.g. Accessibility Service privileges

- The C2 backend matches the theme of the dropper app (e.g., a working fitness-themed website for a workout-focused app)

- The configuration file delivered by the C2 to the dropper contains filter rules based on device model. “[The] actors have set restrictions, with mechanisms to ensure that the payload is installed only on the victim’s device and not on testing environments. To achieve this, criminals use a multitude of techniques, which range from location checks to incremental malicious updates, passing by time-based de-obfuscation and server-side emulation checks,” the researchers noted.

Potential victims are tricked into downloading the initial droppers because the usual advice for vetting apps – checking out user comments, avoiding apps with a small number of downloads, checking out the app website – doesn’t work here.

“Actors behind it took care of making their apps look legitimate and useful. There are large numbers of positive reviews for the apps. The number of installations and presence of reviews may convince Android users to install the app,” they concluded.

Android users who suspect they might have been infected through these campaigns should review the IoCs (the dropper apps’ names and packages names) and see whether they have one of these packages installed on their smartphones.

Credit: Source link